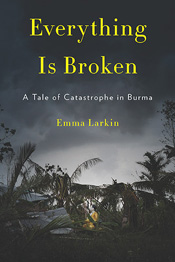

Title: Everything is Broken: A Tale of Catastrophe in Burma

Author: Emma Larkin

Genre: Literary Journalism

Year: 2010

Acquired: For review for TLC Book Tours

Rating:

One Sentence Summary: After a devastating cyclone hits Burma and the corrupt totalitarian regime refuses international aid claiming everything is fine, journalist Emma Larkin returned to the country to chronicle life after the storm.

One Sentence Review: Despite a compelling story and careful writing, Everything is Broken lacks the type of forward momentum that characterizes truly great narrative nonfiction and therefore left me a little disappointed.

Long Review: Everything is Broken by Emma Larkin is a book that had a lot of things going for it. The topic is a terrible natural disaster and criminally neglectful government response. The author had exclusive and difficult access to her subject and people impacted by the disaster. The stories that make up the bulk of the book are sad, frustrating, and, occasionally, hopeful.

But for all of that, Everything is Broken fell a little short for me because it lacked the sort of overarching “plot” that I think good narrative nonfiction requires.

I should back up a bit. Everything is Broken is the story of what happened in Burma after Cyclone Nargis hit on May 2, 2008. Larkin, a journalist writing under a pseudonym, was previously in the country reporting and writing her first book, Finding George Orwell in Burma. When the cyclone struck, she worked to return in order to report on the aftermath of the storm.*

Unfortunately, that wasn’t quite a focused enough mission statement to hang a book on. As I read, I never felt like I knew where the book was going or what it was trying to accomplish and I found that very distracting. I need and expect focus and forward narrative momentum from great narrative nonfiction, and this didn’t quite have it.

Part of this critique isn’t the book’s fault – at some level there is no beginning, middle, and end to something like a natural disaster. And in a country like Burma, where the government is entirely corrupt and the people have no recourse for their grievances, it’s probably as hard to find closure as it is to get any real information.

Certainly, I wouldn’t have wanted Larkin to artificially create some sort of ending for the story. That wouldn’t have been true and probably wouldn’t have been good. But I did want a more clear focus and direction for the story I was being taken on.

But I don’t want this critique to take away from some of the really remarkable parts of this book. Burma is a difficult place to report from at any time, made even worse by the cyclone. Larkin is able to collect truly devastating stories from the people affected, and eloquently compares what she sees to the clearly false information being propagated by the government in their official news source, the New Light of Mynamar. As she explains,

In the hothouse environment of Rangoon, where the truth was malleable and facts and figures could be plucked out of thin air, anything seemed possible. As there are so few reliable sources of news in Burma, rumors take on an added significance and act as a barometer of people’s hopes and fears. What becomes important in this context is not whether they are true but whether people believe them to be true.

In fact, some of my favorite parts of the book were learning about how official news in Burma works and how easily the press can be manipulated, not because I liked it but because it fascinates me in a weird stare-at-a-car-accident sort of way.

Learning about some of the absurdity of the regime was also interesting, if extremely frustrating. For example, after the cyclone hit the government put out numbers about casualties, based on basically no information but with extreme detail — exactly 136,804 buffalo or 1,250,194 chickens. Of this, Larkin says,

Though these numbers may have been estimates based on farm animals registered before the cyclone, they were obviously fictitious — no one could have possible been around the entire delta counting and confirming the death of each missing chicken. While the rest of us patched together disparate eyewitness reports and scrambled around after intangible facts, the generals were producing solid answers. The image they were trying to portray seemed to be one of omniscient and supreme power: The regime knows everything, even that which is, ultimately, unknowable.

As you can see, the writing in the book is very good. Larkin has a natural-feeling style, and is able to integrate herself and experiences into her reporting without making the story about her. She uses her experiences as a device to explain how the regime works, rather than using her experiences as center of the book, which can sometimes be a challenging balancing act for journalists using “I” in their writing.

So while I was a little disappointed by Everything is Broken, I’m intrigued enough by the subject and Larkin’s approach that I’ll be moving Finding George Orwell in Burma — a book that has a much clearer sense of story — up on my “to read” list.

*If you want some more background on this, Wendy (Caribousmom) did a comprehensive post with videos and links to information about Burmese politics and this disaster that I urge you to check out.

Other Reviews: Word Lily | The Little Reader | Heart 2 Heart | Cafe of Dreams | Books Movies and Chinese Food | Book Addiction | Lit and Life | Caribousmom |

Other Reviews: Word Lily | The Little Reader | Heart 2 Heart | Cafe of Dreams | Books Movies and Chinese Food | Book Addiction | Lit and Life | Caribousmom |

If you have reviewed this book, please leave a link to the review in the comments and I will add your review to the main post. All I ask is for you to do the same to mine — thanks!

Comments on this entry are closed.

Oooh interesting I did not know this book existed but now I do. I’ll have to add it to that old TBR pile. My dad comes from Burma so I have a special interest. 🙂

Fiona: Wow, that’s a cool connection. I hope you get a chance to read the book.

Sounds like an interesting book, even if it does lack any kind of direction. I’ll have to check for this one, as I haven’t read a lot on Burma to date.

Amy: I hadn’t read much on Burma either, so that part was very interesting to me. It’s a place that deserves more attention.

Thank you! ‘Focus and forward momentum’ are the exact terms I’ve needed for two recent reads that left me disappointed. Both were extremely lacking in these books. Like you, I need the plot to be going somewhere or I’m just not that interested.

Trisha: Focus and momentum are two things I feel like I’m especially picky about. I think it comes from my journalism training — things always need to be going somewhere.

I certainly agree that this book lacked in the realm of plot or momentum. I think I might not call it narrative nonfiction, but rather (simply) nonfiction, because of that. It conveyed the facts well, and the writing wasn’t overly dry, but it didn’t have an arc. It wasn’t exactly what I expected, but I did find the book powerful and informative.

Word Lily: That’s a good point — maybe assessing it as narrative nonfiction was a little bit unfair. But I felt like the use if “I” coupled with the way Larkin followed her own explorations around Burma to give the books some general shape pushed it enough toward narrative nonfiction that the critique is at least somewhat justified.

But maybe if I’d had a little different expectations, I wouldn’t have been disappointed because in most other respects I thought it was as good book.

I agree with WordLily that I think this probably fit best in the realm of straight nonfiction vs. narrative (or creative) nonfiction. Although I loved the book and was very moved by it, I agree that it wasn’t a linear story with lots of forward momentum…Larkin goes back and forth in time to uncover what has happened in Burma…and sometimes leaves the Cyclone to delve into other human rights issues which add depth to what happened with Nargis. This was a really great review, Kim…you pointed things out about the book which other reviewers didn’t…And thank you for the shout out to my tour post too 🙂

Wendy: Like I said in the previous comment, I think the use of “I” and the way she framed the book — as her going to Burma to report — shifts it a little bit. But I think it’s a good discussion about what genre the book would fit, and whether expecting it to be more narrative was expecting something the book wasn’t trying to do.

I suspect one of the reasons I brought it up so much in the review is that I think my perspective as a journalist makes me pay more attention to things like that than the other reviewers on the tour might have — I’m glad to be able to have pointed out something a little different even if there’s some disagreement 🙂

Oh, I also meant to add that I included a link to your review on my review 🙂

Too bad this didn’t live up to its potential.

bermudaonion: Yeah, a bit, but it was still good, just not great.

Thanks for reviewing this book. For whatever reason, just the other day I was thinking about this recent tragedy. Too bad the book was a bit of a disappointment. Thanks for reviewing it, though !

Maphead: I’m a little embarrassed to admit I didn’t know much about this tragedy before reading the book, so for that I was really appreciative.

I almost put this one down in the first part–so slow moving. I just started thinking ” I get it already; move on!” I did like the history part and the third part was what I was looking forward to all along.

Lisa: I agree — I think the book improved as it went along. The first part was frustrating, both as a reader and because of how little everyone was able to do to help people.

I’m sorry this one didn’t work for you as well as you’d have liked, but it sounds like there were quite a few redeeming qualities at least. The topic is fascinating to me and I do hope to read this at some point. I’ll keep in mind the lack of structure though …

Heather J: Yes, despite my criticism the book does have a lot going for it and I do recommend reading it. I don’t know a lot about Burma, but the book really made me want to learn more because it seems just absurd that something like this could happen.