While I don’t do a ton of author interviews here on the blog (I do plenty of interviews as part of my day job!), I always get a thrill when I have the chance to ask more experienced writers and journalists to talk a little bit about their craft.

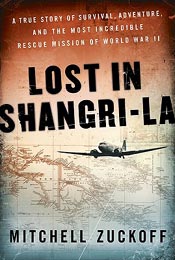

Mitchell Zukoff, the author of this year’s winner of the Indie Lit Award for Nonfiction, Lost in Shangri-La, was gracious enough to answer questions put together by the nonfiction panel including how he found the topic the story, what it was like to travel to New Guinea during research, and one piece of writing advice he offers his students.

How did you decide upon this particular topic for your book? What led you to this story?

I was researching a different World War II story when I came across an article in the Chicago Tribune from June 1945 that knocked me for a loop. The article explained that a military plane had crashed in an impossibly remote valley of New Guinea that had been nicknamed Shangri-La. Twenty-one people had been killed, but three survivors – two soldiers and a beautiful member of the Women’s Army Corps – were awaiting rescue by giant gliders that were supposed to be dropped to the valley floor, then snatched back into the air by passing planes.

I was researching a different World War II story when I came across an article in the Chicago Tribune from June 1945 that knocked me for a loop. The article explained that a military plane had crashed in an impossibly remote valley of New Guinea that had been nicknamed Shangri-La. Twenty-one people had been killed, but three survivors – two soldiers and a beautiful member of the Women’s Army Corps – were awaiting rescue by giant gliders that were supposed to be dropped to the valley floor, then snatched back into the air by passing planes.

I wouldn’t be much of a journalist if I hadn’t stopped everything to read that article! I was stunned that I had never heard about this, and apparently no one else had, either. I knew immediately that it was worth pursuing, but I didn’t know – and I wouldn’t know for more than a year – whether I’d be able to collect enough documentary material and human sources to turn it into a book.

In your introduction you mention coming across a host of documents about the crash – a journal, photographs, scrapbooks, and film. What was the most exciting piece of evidence that surfaced?

On one hand, it’s probably the diary that Margaret Hastings wrote about her experiences. That gave me incredible material to work with. But the real breakthrough moment during the early phases of the research was finding that Earl Walter, who led the paratrooper team into the valley, was still alive. Earl was able to give me a firsthand account of these events, and he generously shared not only his memories but also his scrapbooks, the journal he kept during the mission, and dozens of photographs he took that now appear in the book.

In 1945, Earl was a dashing young paratrooper captain eager to get into the action of the war. His father was leading a group of Filipino guerrillas in the jungles of the Philippines, and Earl wanted to prove that he was his father’s equal. Earl was 88 when we met, and there was still a bit of that gung-ho young man in him. Although his short-term memory wasn’t strong, he remembered every detail of the Shangri-La rescue mission. In fact, he described the people, places and events in rich detail, in ways that no documents could match. I’m happy to say that Earl is still alive, and I consider him a friend.

You also traveled to New Guinea during your research – what was the most memorable part of that experience?

Climbing the mountain where the crash took place was the most powerful emotional experience of this project. After spending years thinking about and writing about this plane crash, here I was amid the wreckage – which is still there. I was able to look through what was left of a window opening in the fuselage and think, “One of the crash victims probably looked through this window moments before the crash.” While I was digging through the wreckage, my guide and I found a small piece of human bone. We held a brief service then buried it with a marker nearby. I already felt a great responsibility to tell the story of those who died and those who lived, but that discovery drove it home with me even more.

What was your process to go from collecting research to outlining to writing the book? How did you keep yourself organized with such an extensive collection of documents to work with?

The best way I know of to stay organized on a narrative nonfiction project is to create an incredibly detailed chronology. I keep track of everything with this document – it serves as sort of an index to all my files. In this case, I focused most of the chronology on the spring and summer of 1945. Each time I came across a new piece of information – a source, a document, a photograph – I plugged it into the chronology. The result is a twofold benefit: it helps me to keep track of everything, and it shows me where pieces of information fit together when I start to write.

What is one piece of writing advice you like to offer your students?

Just one? I wouldn’t be much of a teacher if I only had one piece of advice! OK, seriously, if we assume that they’re already reading great work – both fiction and nonfiction, regardless of what they want to write – I urge them to focus on the rhythms that emerge over the course of an entire piece, whether it’s a 5,000-word magazine story or a 100,000-word book.

As many people before me have said, writing and music have so much in common. They activate many of the same parts of our brains. To sustain readers’ interest and attention in a book, a writer has to vary the rhythm, the pace, the volume of the work in different sections, as appropriate. It might be OK to bang the bass drum at one tempo and volume over the course of a three-minute single. But if you want people to listen to the whole album, take advantage of the entire range of dynamics available to you.

What was your favorite part of writing this book?

Without question, my favorite part has been the reaction of readers. Writing is hard work. I love it, and I wouldn’t want to do anything else, but it’s not an activity I think about in terms of “favorite” parts. It’s incredibly satisfying when a reader – someone who doesn’t know me, so they’re not just being nice – tells me that he or she loved spending time with the people I wrote about.

Thanks again to Mitch for taking the time to answer our questions. If you haven’t read Lost in Shangri-La, you should remedy that situation right away. It’s a fantastic book!

Comments on this entry are closed.

Great interview! I’ve heard this book is fantastic and I hope to read it soon.

Great interview! It was fun to read his answers after having read the book. 🙂

Yeah, I thought that was fun too. Especially thinking about talking with Earl Walter, and knowing how much he added to the story.

Nice interview. Sounds like a bit I need to track down. I love narrative non-fiction.

It’s a really excellent book, a perfect example of what great narrative nonfiction can be.

Great interview! I love the idea of writing and music being so similar.

I really enjoyed this book…reading his answers to these questions added to that. Thanks!

I saw this book at my library this past weekend and picked it up – I think I must have seen it on your blog and noted it in my head. Great interview – and that is so fantastic that he was able to interview someone who was part of the rescue.

Yeah, I thought that was a very cool part of the story. In the book he doesn’t reveal who the person he spoke with was until the very end, which makes it a sort of cool detail to discover.

Great interview! Thanks for orchestrating all of this so we can get inside the head of this author. I loved this book and I’m really pleased that you were able to interview the author. Nicely done!

Me too! It’s always fun to get the chance to talk with an author of a book you loved (especially one as popular as Lost in Shangri-La.

Just finished reading and listening on my kindle. Really enjoyed it. And as a side note My daughter was married to Richard Walter from New Jersey and has 3 children. The youngest is name Tanner and looks a lot like Earl from his picture on the internet. Tanners Gpa and Richard’s father was named Earl also. I sent it all on to Tanner to check out.