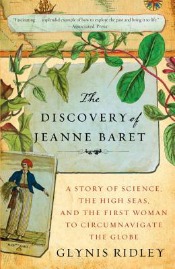

Title: The Discovery of Jeanne Baret

Author: Glynis Ridley

Genre: Narrative Nonfiction

Year: 2010 (Paperback 2011)

Acquired: From the publisher for review consideration

Rating:

Summary (Source): The year was 1765. Eminent botanist Philibert Commerson had just been appointed to a grand new expedition: the first French circumnavigation of the world. As the ships’ official naturalist, Commerson would seek out resources—medicines, spices, timber, food—that could give the French an edge in the ever-accelerating race for empire.

Jeanne Baret, Commerson’s young mistress and collaborator, was desperate not to be left behind. She disguised herself as a teenage boy and signed on as his assistant. The journey made the twenty-six-year-old, known to her shipmates as “Jean” rather than “Jeanne,” the first woman to ever sail around the globe. Yet so little is known about this extraordinary woman, whose accomplishments were considered to be subversive, even impossible for someone of her sex and class.

Review: There’s nothing like finding a book that tells a previously unknown or misunderstood story, and the tale of Jeanne Baret is definitely one of those. Set on the high seas, and full of romance, intrigue and adventure, it’s exactly the sort of narrative history book that I find deeply fascinating.

And for much of The Discovery of Jeanne Baret, author Glynis Ridley manages to tell a fantastic story, woven together with a limited and obviously biased set of sources. The Jeanne of Ridley’s account is independent, smart, daring and sympathetic. And her major contributions to our understanding of botany — despite the obstacles she faced from her master and lover Commerson and the situation she found herself in at sea — are well worth recognizing. On the whole, I really enjoyed reading the story.

Where this book struggled, for me, was in the parts where you could see how it was being put together (you know, that old joke about sausage and politics). Because Baret never wrote her own account of her life and voyage, Ridley is forced to read between the lines of the number of unreliable narratives available to find Baret’s story. There are a lot of “Perhaps Baret felt…” or “Certainly, Baret would have thought…” moments that leave many more questions than answers. Although I appreciated the way Ridley showed where she was making assumptions and what her logic was, there were serious moments when I didn’t agree with her conclusions or the way she moved from assumption to fact as the narrative continued.

That’s not very clear, so maybe an example will help. In the book, Ridley argues that the conventionally accepted story about how Baret’s gender was exposed on the voyage is wrong. Most narratives, based heavily on the account of the voyage written by the captain, accept that Baret was discovered when the ships stopped on Tahiti. In that version of events, Tahitian natives recognized her as a woman and Baret had to call for help to save herself from a sexual assault.

Instead, Ridley agues that Baret’s identity was really discovered some time later on the island of New Ireland. After convincingly analyzing three others accounts of the events and showing that Baret was probably discovered here , Ridley goes on to suggest — on what appears slim evidence — that Baret was gang raped by the crew and one of the well-respected men of rank on the voyage.

Although Ridley notes that it’s difficult to accuse a man of rape when he’s long dead and can’t defend himself, she then goes on with the story basically declaring that the rape happened as she assumed it did. She writes that Baret took to her cabin in an opium-induced sleep for days afterwards. That’s a leap I’m not necessarily comfortable with, and one that made me more skeptical of earlier guesses about Baret and her life.

(Fyrefly of Fyrefly’s Book Blog had a similar reaction to the storytelling style. including the rape conclusion and Ridley’s tendency to write about Baret’s emotions as if they were fact, even though there’s little or no documented evidence for some of those conclusions. Her review is great. Go read it!)

Having said that, those types of narrative leaps didn’t bug me enough to make me regret reading the book or recommending it as a good read. If anything, they made me even more curious to read about Jeanne Baret and find out more about her. She’s a fascinating, under-recognized woman who defied the expectations the world had for her and made her own way in the world. There’s a lot to admire about that, and her story — however difficult it is to put together — is worth reading.

Other Reviews:

If you have reviewed this book, please leave a link to the review in the comments and I will add your review to the main post. All I ask is for you to do the same to mine — thanks!

Comments on this entry are closed.

I have to admit I am a bit curious about this book. The reviews have been mixed, but the subject is just intriguing!

The subject of the book really does help. Even though it’s hard to know much about Jeanne, she seems like a fascinating woman. And the things she was able to accomplish, at the time she was living, are pretty incredible.

I’m generally not a fan of books that speculate like that. This one probably isn’t for me.

No, probably not. There’s no way to read this and not have to think about how much speculating is going on in the story.

Sometimes I can get very bogged down when reading non-fiction — it’s very easy for me to stop and think, “Okay, but how does the author know that?” I have no such issues with fiction, of course, and maybe that’s part of why I tend to stick with novels. But I’m still steadily trying to break away from that!

Jeanne Baret is someone about whom I know nothing, and her life definitely sounds extraordinary, so this might be one I’d check out.

Yes, that can happen to me too, although I think I have a pretty deep sense of trust for most authors when I go into a book. I don’t expect they have an agenda that might impact how they choose to tell a story until that agenda becomes apparent. I think the sections of this book I struggled with most were when the author’s agenda became really clear, and I disagreed with her conclusions because of it.

Hahahaha, I can’t stand it when authors draw too often from the “[Biography subject] must have felt/thought” well too many times in one book. I have a very very limited tolerance for it. I respect it much more when they just say they don’t know.

It’s a really hard thing to balance. It’s hard to tell a good story without being able to write about how the people felt, but without diaries or other documentation, it’s impossible to know those things or not speculate. I’ve a decent tolerance for it, but this time it felt like too much.